The 8 x 10 Work 2

Where we left off with The 8 x 10 Work last time was that I knew I had a problem and was questioning how I was going to solve it. Hundreds if not thousands of 8 x 10 negatives, processed, but not printed, not scanned and, unless I did something, never to see the light of day. Okay, this is not solving the world's major issues, but is important to me. Think about it this way: lug around that super big beast of a camera, sometimes hiking for several miles with it over my shoulder to make one picture. Process the film, four sheets at a time, in trays, in total darkness and then not see it as a print?

Let's back up a little bit. Lest you assume I was totally clueless back then, I was constantly making prints from what I shot. I was a darkroom printer for most of those years and had my own darkroom at Northeastern (part of the perk of being a professor there), and was regularly processing film and printing with an 8 x 10 enlarger. I had shows of that work; a big one at Panopticon Gallery in about 1990 (thank you, Tony!), another on the Vineyard in 1994, another in Camden, Maine one summer, another at the RISD Museum, another at the Canterbury Shaker Village in NH and so on. I would often present work to local museums like the DeCordova, the Fogg, the MFA, even MOMA and the National Gallery, and so on of portfolios made from 8 x 10 negatives. But a good print from an 8 x 10 negative usually took hours to make and it wasn't unusual for me to need a whole day just for one photograph. So being prolific got me in trouble as I was increasingly printing highly selectively from what I shot. And falling behind. I remember one summer teaching in Italy, coming back with 700 sheets of film shot. It took me six months just to process the film.

So let's move up to the present, and perhaps there's a lesson in here for some of you as well as for myself. Now I am shooting solely digitally. OK. But I have this huge backlog of analog negatives in 8 x 10 and yes, also in 2 1/4 (a story for another time). Some of this work is good and deserves at least some exposure. Do I allocate serious time to making the scans? Honestly it isn't really the scan making that is so time consuming. It is the cleaning that takes sometimes hours per image. Assuming I can bear this (I cannot, by the way) I would be taking time away from what I clearly love and that is shooting. My solution? Drum roll, please: hire an assistant.She is a senior at Lesley, and her name is Hannah. Hannah had no previous scanning experience but has proved herself to be valuable beyond words in that she is meticulous, careful and precise in the handling of my negatives. And, a very big and, she is very good at cleaning and making the images RTP (Ready to Print). Will I get through all the negatives in just one summer? No, but I have begun the project and have paved a way for future work in its cause. We have started and it is good to finally begin to see these pictures after all these years.

Finally, I am sure some of you are thinking why not just print the negatives normally, they way they were intended, in the darkroom? Two reasons: I don't have a darkroom anymore and don't ever want to print in one again, and two, we've already covered the need to scan the negatives anyway, why not do it right and then give myself the option of printing them any size on up to several feet by several feet? Don't think inkjet prints are as good? Don't get me started on that one as I know they are as good as gelatin silver prints and have proven it. That's why.

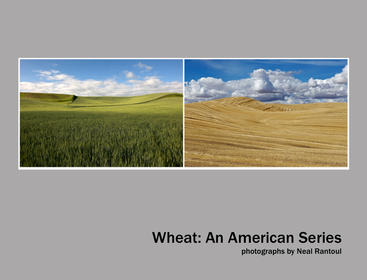

BTW: You've probably guessed but the photographs interspersed throughout these two posts are from scans of some of my 8 x 10 work. More to follow.

As always , thanks for reading and..... stay tuned.